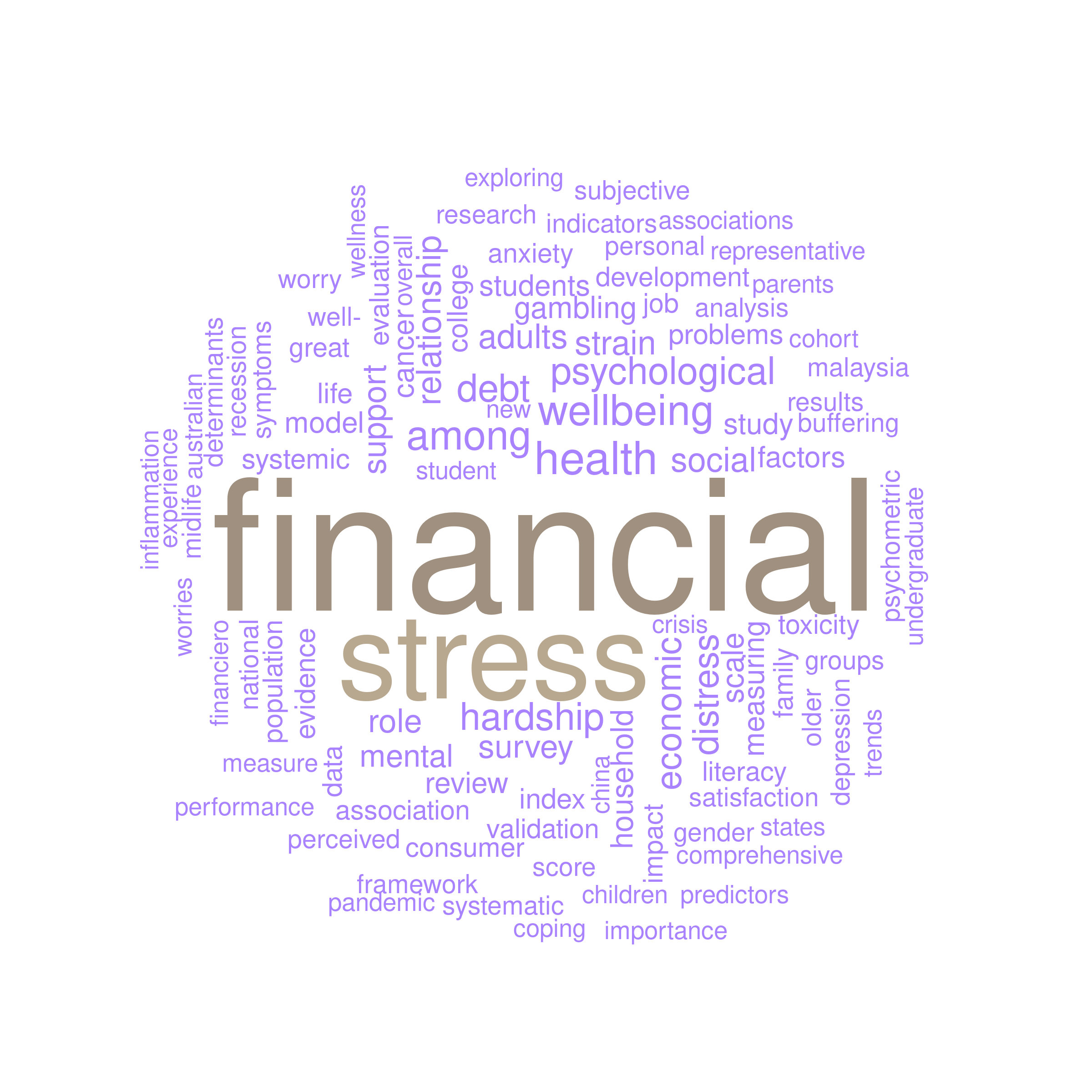

Initial validation of the dyadic coping inventory for financial stress.

Thoughts

Citing Northern et al. (2010), says that ‘individuals experience financial stress when they are unable or are afraid of being unable to meet their financial responsibilities’.

Connects with: @northern2010

Annotations

falconier2019 - p. 367

Individuals experience financial stress when they are unable or are afraid of being unable to meet their financial responsibilities (Northern, O’Brien, & Goetz, 2010), and this seems to be a common experience among adults in the United States.

falconier2019 - p. 367

At the couple’s level, financial stressors can be considered dyadic in nature as both partners tend to be affected. When one partner experiences financial stress, so does the other partner, due either to crossover effects and/or the fact that both partners are experiencing the same financial stressor

falconier2019 - p. 368

Considering that financial stress is common, typically affects both partners, and has direct detrimental consequences on the couple relationship and indirect consequences on parenting and child adjustment, it is important to understand how partners cope with financial stress. Among the many available models to understand couples coping with stress, also known as dyadic coping, the systemic‐transactional model (STM; Bodenmann, 1995)

falconier2019 - p. 368

onsistent with the STM conceptualization of stress and coping in couples, Bodenmann developed the Dyadic Coping Inventory (DCI; Bodenmann, 2008), a self‐report questionnaire specifically designed to measure dyadic coping.

falconier2019 - p. 368

STM, which is an extension of Lazarus and Folkman’s transactional stress model (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984) to the couples context, is the conceptual framework that has guided most of the studies on couples coping with stress, also known as dyadic coping (for a review, see Falconier et al., 2015).

falconier2019 - p. 368

According to STM, partners may cope with stress individually (e.g., engaging in a recreational activity, self‐talk, seeking advice, etc.), and/or they may seek and/or receive assistance from their partners to cope with stress (e.g., providing emotional or instrumental support, engaging in relaxing activities together, etc.). Because one partner’s stress usually affects the other partner’s, couples tend to communicate their stress to one another and engage in processes of mutual support and coping.

falconier2019 - p. 369

The DCI is a self‐report questionnaire that was developed to measure all the dimensions proposed by STM. It initially included 55 five‐point Likert‐scale items (1 = very rarely, 5 = very often; Bodenmann, 2000), but as a result of factor analyses, the questionnaire was subsequently reduced to 41 items first and later on to 37 items (Bodenmann, 2008).

falconier2019 - p. 369

These dimensions result in the following 12 scales: (1) Stress Communication by Oneself; (2) Stress Communication by Partner; (3) Emotion‐Focused Supportive DC by Oneself; (4) Emotion‐Focused Supportive DC by Partner; (5) Problem‐Focused Supportive DC by Oneself; (6) Problem‐Focused Supportive DC by Partner; (7) Delegated DC by Oneself; (8) Delegated DC by Partner; (9) Negative DC by Oneself; (10) Negative DC by Partner; (11) Emotion‐Focused Common DC; and (12) Problem‐Focused Common DC.

falconier2019 - p. 370

The DCI was designed to measure how couples cope with stress in general and not with a specific set of stressors.

falconier2019 - p. 372

The DCIFS is a 33‐item self‐report inventory designed to measure how partners cope with financial stress.

falconier2019 - p. 372

The 10‐item Dyadic Satisfaction subscale was used in the present study to measure relationship satisfaction and evaluate the predictive validity of the DCIFS. The Dyadic Satisfaction subscale assesses how satisfied a partner is within his/her couple relationship (e.g., How often do you think that things between you and your partner are going well?). Higher total scores indicate higher relationship satisfaction. In this sample, the internal consistency of the Dyadic Satisfaction subscale was α = 0.71 for women and α = 0.73 for men.

falconier2019 - p. 372

Psychological Aggression subscale of the CTSR was used to measure psychological aggression and evaluate convergent validity. This is an eight‐item Likert type scale designed to measure the frequency with which respondents engage in psychologically aggressive behaviours (e.g., insulting or swearing)

falconier2019 - p. 373

For evaluating the measurement invariance (MI) of the DCIES factor structure across gender, multiple‐group CFA’s were conducted for independent male and female subsamples

falconier2019 - p. 374

The initial four‐factor model (Stress Communication, EmotionFocused Supportive DC, Problem‐Focused Supportive DC, and Negative DC) did not show a good fit of the data for either the DC by Oneself or DC by Partner aggregated scales for either gender’s reports

falconier2019 - p. 374

The third model tested included these respecifications and indicated a good fit to the data for both men and women and for both by Oneself: men’s reports: χ2 (13) = 14.97, p = 0.30, CFI = 0.99, SRMR = 0.04, RMSEA = 0.03 (0.00–0.09); women’s reports: χ2 (13) = 21.30, p = 0.06, CFI = 0.96, SRMR = 0.04, RMSEA = 0.07 (0.00–0.12); and by Partner: men’s reports: χ2 (13) = 14.18, p = 0.36, CFI = 0.99, SRMR = 0.04, RMSEA = 0.02 (0.00–0.09); women’s reports: χ2 (13) = 23.79, p = 0.03, CFI = 0.96, SRMR = 0.05, RMSEA = 0.07 (0.02–0.12) aggregated scales. Except for women’s reports on the DC by Oneself aggregated scale Δ(χ2 (16) = 22.82, p > 0.10), Model 3 was significantly better than Model 2 for all the other aggregated scales: men’s reports of DC by Oneself: Δχ2 (16) = 35.73, p < 0.01; men’s reports by Partner: Δχ2 (16) = 52.21, p < 0.001; women’s reports by Partner: Δχ2 (16) = 36.53, p < 0.01), with factor loadings ranging from0 .58 to 0.90 (Figure 1)

falconier2019 - p. 374

As Model 4 inTable 2 shows, fit indices for a two‐factor model (Emotion and Problem‐Focused Common DC) for both women’s and men’s reports showed a good fit of the model to the data: men’s reports: χ2 (4) = 5.92, p = 0.20, CFI = 0.99, SRMR = 0.01, RMSEA = 0.06 (0.000.15); women’s reports: χ2 (4) = 12.18, p = 0.01, CFI = 0.98, SRMR = 0.02, RMSEA = 0.12 (0.04–0.20). Given that the model specified showed good fit to the data and was conceptually driven, no respecifications were made.

falconier2019 - p. 376

The internal consistency for the total DCIFS was α = 0.79 for men’s reports and α = 0.82 for women’s reports.

falconier2019 - p. 378

Specifically, results demonstrated good data fit for configural invariance across gender for DC by oneself (χ2 (14) = 26.19, p = 0.08, CFI = 0.95, RMSEA = 0.08, SRMR = 0.05), DC by partner (χ2 (14) = 25.97, p = 0.09, CFI = 0.96, RMSEA = 0.07, SRMR = 0.05), and CDC (χ2 (4) = 10.95, p = 0.09, CFI = 0.98, RMSEA = 0.09, SRMR = 0.02), indicating that factorial structure was confirmed across gender.

falconier2019 - p. 378

The non‐significant difference between configural, metric, and scalar invariance models indicated equivalent responses of men and women to each item of each subscale