How to navigate in this website

Hey, Altay! Finally, the review is done. I compiled everything into a website to make it more didactic. Sorry to use English. I decided to keep it this way in order to stay consistent to literature and terminologies.

This website works just like Wikipedia:

- By clicking over hyperlinked words, you open up their notes to explore the content. I’ve built some types of notes:

- Source notes: named after each article first author, they contain the highlights I made while reading them

- Scale notes: store explanations about an operationalization of a concept

- Theory notes: concise description of a seminal theoretical framework that was used at least one time to discuss financial stress-related subject

- Concept notes: these notes condense studies definitions, related theories, measurements, determinants, and outcomes, based on terminology alone

- Supplementary notes: keeps a table, a figure or another type of material

- To go back use the ‘Backlinks section’ at the right lane of the page or the navigation breadcrumbs over the page title

- It’s possible to explore the network of notes and concepts by clicking the graph button, inside the ‘Graph View’ tab, on the right-superior corner. There, you’ll see nodes with different colors. They follow the note types: source notes are green, scale notes are blue, theory notes are yellow, concept notes are red, and supplementary notes are white.

The last point is this: I planned to write the whole review in this page, but as the content analysis of terminologies is demanding more time than I planned — yes, I secretly wanted to brought something different to the review — I decided to simply link here the pages at the proper sequence.

A proper review of financial stress posits a core problem right at the beginning, which anyone might face, regarding terminology. Such issue may arise specially when considering a long time window which makes possible to examine how vocabulary changed over decades. Also, in order to cover different research questions and conceptualizations, a broad scope of populations and countries were considered. In total, 137 articles were included, totalizing more than 540k participants (apart from big data samples) and over 60 countries. Considering all studies, 17 terms on ‘money-related problems’ — a wildcard vocable to represent the broad meaning underlying all terminologies on the agenda — were defined. Based on a rol of 38 theories, the articles suggested different models and frameworks while validating 19 formal scales, besides a great number of various ad-hoc measures. Detailed results with key findings, scales, and others are presented on Table 1.

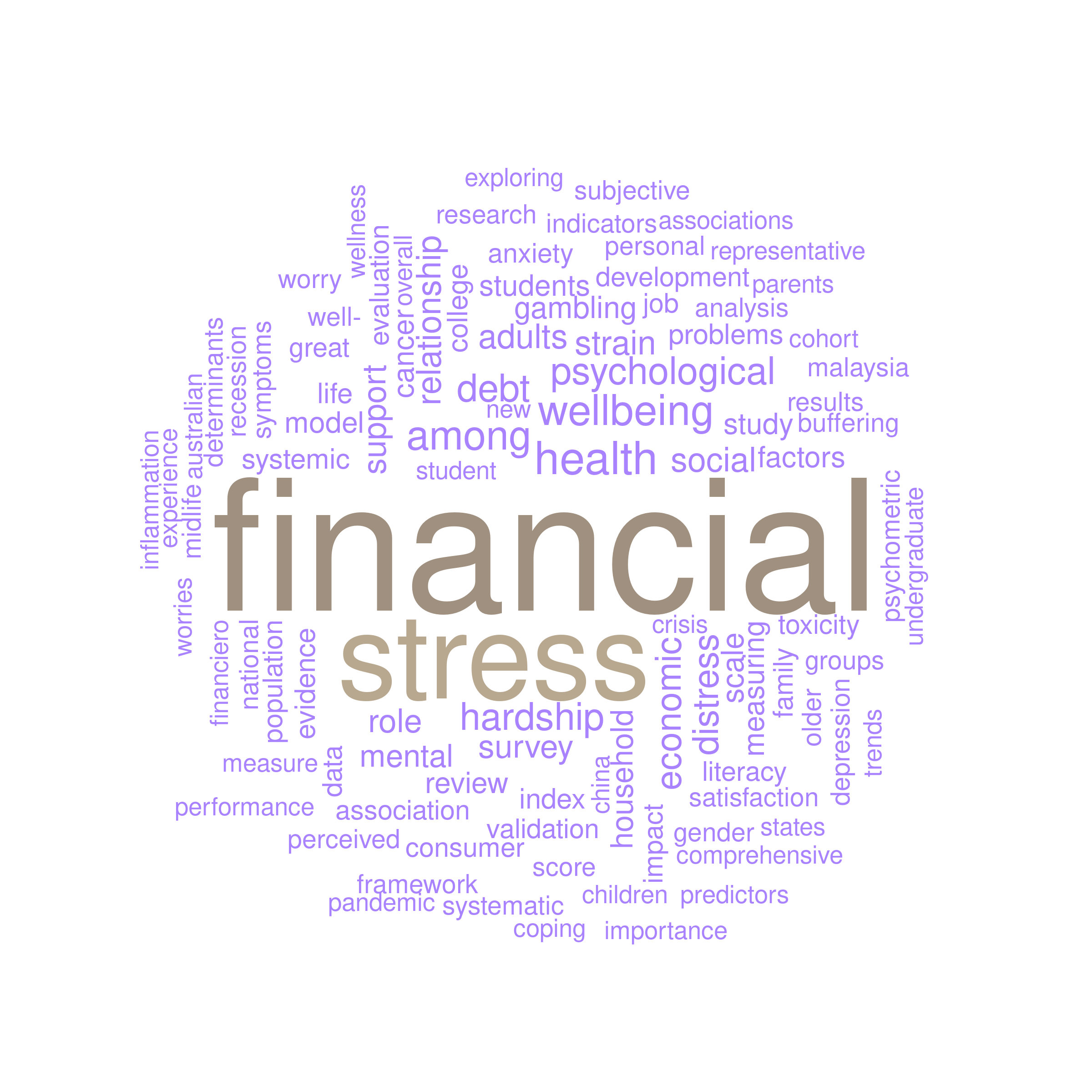

The most prevalent design was cross-sectional (n=84, 61.3%). Almost 45% of studies included participants from USA (n=61), followed by Australia (n=9, 6.6%) and Netherlands (n=5, 3.6%). The main unit of analysis was individual adults (n=54, 39.1%), next to countries (n=20, 14.6%) and households (n=14, 10.1%). 2021 was the year with greater number of publication in our sample (Figure 1). The most cited word on titles was “financial” (n=147), followed by “stress” (n=88) and “health” (n=21). The bigram “financial stress” was mentioned 74 times, above “financial hardship” (n=12) and “financial strain” (n=10).

Given the extensive literature on money-related problems many terms emerge with similar meaning, and analogous words have divergent meanings. In fact, ‘financial stress’ is just one in a myriad of closely related expressions. The lack of unicity, apart from effortful nomological attempts, is a barrier to the establishment of proper interfaces between scientific fields. At least from an ontological perspective, this panorama is shared, from higher to lower-levels of relationships, between economists, anthropologists, sociologists, and psychobiologists. For instance, there was a total of 45 distinct definitions for “financial stress” in our sample; 11 for “financial strain”; 9 for “financial hardship”; and a fluctuating amount for “financial toxicity”, “financial threat”, “financial scarcity”, “financial worry”, “financial rumination”, “financial distress”, “financial deprivation”, “financial anxiety”, “economic worry”, “economic stress”, “economic strain”, “economic hardship”, “economic distress”, “economic deprivation”, including “economic anxiety”.

All of these money-related problems aliases cross-relate with each other not only through bigram combinations, but via similar word-usage in their definitions. Below we discuss how authors ground their object of study and structure their frameworks, while comparing their ideas. At first glance, nevertheless, it’s possible to establish a clear division: some authors belong to a macrosystemic field of investigation, the realm of emergent effects on scaled financial trades between economic agents — companies, societies, states, countries, and blocs. The other niche is occupied by microsystemic studies, in which relationships amidst individuals inside their household is taken into account, as well as the external and internal mechanisms that favors the rise of money-related stress in a person.

Microsystemic money-related problems

Please, read this!

As I previously said, this section is under construction because of the content analysis, so I’ll link you to my concept notes, which I used to brainstorm all articles at once. Another thing I’d like to say: after reading all these articles, while I still don’t know what was your theoretical framework for financial stress when following the cohort, I’ve reached the understanding that a MIMIC model would fit very well this construct.

Each one of these notes are divided in definition, theoretical frameworks, operationalization, determining factors and outcomes, with effect sizes:

- Financial stress

- Financial strain

- Financial distress

- Financial anxiety

- Financial hardship

- Financial preoccupation

- Financial deprivation

- Financial threat

- Financial toxicity

- Economic stress

- Economic strain

- Economic worry

- Economic distress

- Economic hardship

- Economic deprivation

- Economic anxiety

Macrosystemic money-related problems

Defining macrosystemic financial stress

The term “financial stress” have a clear, distinct meaning in the context of macrosystems. This is the case because, differently from the microsystemic perspective, synonyms or alternative bigrams aren’t commonly used. Also, authors agree on a core component: the inherent uncertainty that underlies the phenomenon. The broad definition of @hakkio2009 — financial stress as a “period of disruptions to the normal functioning of financial markets” — was adopted by many authors despite the time gap (@bonato2024, @monin2019, @fava2024). It also inspired @ilesanmi2020 to describe financial stress as an impairment to “smooth functioning of the financial system’s ability to provide financial services”. Other authors branch off to the specific approach of @oet2015, which suggested financial stress is an accumulated pressure over elements of the financial system, and @balakrishnan2009 added that the resilience to intermediate these shocks is impaired. There is consensus the aforementioned turmoil are determined by numerous, co-dependent stressors (@cardarelli2011, @kremer2021, @chavleishvili2023, @chavleishvili2025), which emerge from increased uncertainty among economic agents (@illing2006). Ultimately, illiquidity and risk rises, widely damaging the economic structure and leading to inflation, high interest rates and stagnation (@rooj2025, @huotari2015, @andriansyah2025, @duprey2017, @hollo2012).

Why macrosystemic?

In the economic literature, authors commonly use ‘systemic financial stress’ to refer to system-wide financial stress that affects nations and societies. We use ‘macrosystemic financial stress’ to distinguish it from stress that occur on smaller systems, such as individuals, households, neighborhoods

Theoretical grounds of macrosystemic financial stress

Economic theories are used by authors not only to ground a definition for financial stress but to guide its measurement and explain its dynamics. As previously stated, uncertainty is a core phenomenon on the stress generation, which is supported by the Knightian Uncertainty and the Rare Disasters theories. @hakkio2009 proposes, relying on the former, that unexpected market changes reveal uncertainties with an incomputable risk, which ultimately favors shocks. On the basis of the latter, @fava2024 explains the possibility of large-scale disasters, such as climate changes, may precipitate shocks by risk-aversive behaviors of financial agents. Another contribution comes from the Heterogeneous Market Hypothesis, as @bonato2024 advocate the diversity of market participants can generate unpredictable volatility levels, which ultimately increases uncertainty.

Once perturbations occur, the transmission of stress across the financial system can be explained by the Financial Accelerator Theory. A sufficiently large perturbation may impair economic activity, which retroactively amplifies its severity and range of effect (@cardarelli2011, @hollo2012, @cardarelli2011). Another factor posited by @rooj2025 is the loss aversion from Prospect Theory, which can maximize distribution of negatives financial fluctuations. The progressively greater levels of uncertainty ultimately decreases real options for firms, decreasing transaction rates and impairing market function, as suggested by @mundra2021, on the grounds of the Real Option Theory. In order to achieve increasingly levels of stress, the interaction between its indicators must occur, which its rising is properly framed by the Modern Portfolio Theory. Considering that different shocks occur in the financial system from time-to-time, a certain combination (or portfolio) of variables must rise at the same time. In other words, a high stress means a widely distributed shock (@hollo2012, @kremer2021, @chavleishvili2023, @fava2024). A summary is available on Table 2.

Measuring macrosystemic financial stress

Financial stress in macrosystems are measured through a composite variable called Financial Stress Index (FSI), which aggregates indicators from core stress generating processes: (1) asymmetry of information; (2) uncertainty about fundamental values of assets; (3) uncertainty about the behavior of other investors; (4) willingness to hold illiquid assets (flight to liquidity); (5) willingness to hold risky assets (flight to quality); and (6) concerns about the health of the banking system. A period of financial stress, then, is an interval of time in which the composite variable deviates from a long-term trend to extreme values. Table 3 summarize measures used by studies to compose FSIs. Some measures appear multiple times because they capture more than one process. For instance, credit spreads reflect both information asymmetry and flight to quality. In order to better capture variability and properly account for the relevance of each indicator, authors commonly use a wide variety of weighting schemes to compute their FSI. The main aggregation methods are variance-equal weighting and static principal component analysis (see Table 4).

Determinants of macrosystemic financial stress

The core determinants of macrosystemic financial stress are variables that have indirect or direct effects on its indicators, as well as derived outcomes from different relationships.

Financial linkages

Financial linkages refer to the interconnected relationships and channels through which economic conditions in one system may affect another. @balakrishnan2009 showed increased financial linkages predicted financial stress transmission from advanced economies to emerging countries in different historical moments. Bank linkages, portfolio linkages and direct investments linkages were related to greater FSI records between 1998-2023, and between 2007-2009. The author also found that increased index values of developed countries predicted financial stress severity in emerging countries.

Economic activity

Different economic activities are results or determinants of financial stress. @hakkio2009 showed high FSI values led to decreased Chicago Fed National Activity Index (CFNAI), a proxy for economic activity and inflationary pressure. Both @hollo2012 and @ilesanmi2020 described a decreased industrial production after financial stress episodes in different forecast horizons. Real GDP exhibited bidirectional features. @balakrishnan2009 observed increased global annual GDP growth rate was related to decreased FSI in emerging countries. Alternatively, high stress episodes let to decreased GDP growth in advanced economies, such as USA and EU (@kremer2021, @chavleishvili2023, @chavleishvili2025). @mundra2021 revealed different FSIs predicted falls in investments in India, while @neves2022 explained the severity of impact of economic downturns by output gap shocks is modulated by stress levels.

Lending conditions

@hakkio2009 suggested increased financial stress predicted a restrictive change in credit standards in the USA market. On the other hand, @cardarelli2011 found the greater the real interest rates the greater the severity of results of financial stress through cumulative output loss among advanced economies. The author also measured borrowing ratios, which were associated with greater FSI values and moderated by the stress episode duration.

Primary goods

@nazlioglu2015 identified a relationship between oil market and financial stress in the USA. The author findings suggest FSI Granger-causes changes in oil prices when in high levels. However, there is a reversal in directionality in post-crisis periods, in which oil prices seems to predict FSI variations. In conclusion, @bonato2024 revealed increases global financial stress was associated with realized volatility of different commodities, in many forecast horizons.